Difference between revisions of "Preparing the Budget Section"

(→Question 1: Salaries and benefits) |

(→Question 1: Salaries and benefits) |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

==Question 1: Salaries and benefits== | ==Question 1: Salaries and benefits== | ||

| − | [[Image:Gershowitz1.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:Gershowitz1.jpg|thumb|500px|right]] |

Let us look at how salaries and benefits should be presented. | Let us look at how salaries and benefits should be presented. | ||

Revision as of 22:04, 12 January 2011

Contents

- 1 Writing a Successful Grant: Preparing the Budget Section

- 2 Writing the budget section

- 3 Four questions about the budget section

- 4 Question 1: Salaries and benefits

- 5 Question Two: Matching funds and indirect costs

- 6 Question 3: How specific the budget?

- 7 Major pitfalls

- 8 Open a dialogue with funding agency

- 9 References

Writing a Successful Grant: Preparing the Budget Section

Writing persuasive and successful proposals is an important skill for NGOs, but it is often a daunting task. The budget section and the justification of the budget, which are vital components, are inevitably challenging. There are four specific questions that we will be addressing. We will be getting to them in a short while. But before we do that I want to place the budget section into context.

The typical grant proposal, regardless of its length, contains eight major sections. They normally appear in a set order.

- Need section or justification for the project. First you need to describe the need for the project. That is to give an overall context and to show the gap between the existing situation and the desired situation. That gap constitutes the needs.

- Projected results. Once you establish the needs, you present the results. That is how the projects will narrow or eliminate that gap. What will that project accomplish? What will the results be?

- Methodology. Once you have done that, the third section normally talks about the methodology that you will use to accomplish the project. What exactly is the project going to do? How is it going to work?

- Staff. Once you have talked about the project’s methods, you can describe those who are going to work on the project and show that they are qualified and they have the necessary skill set to do the work that needs to be done.

- Project assessment. The fifth section is essential to every proposal: How will you know if it is working? If it is not working as well as it ought to be working, what can be done to it to make it more effective?

- Budget. Now we come to section six of the eight sections, and that is how much will the project cost?

- Applicant’s qualifications. Following the budget, we normally talk about the applicant’s ability to carry out the project. What is there in your background that would give your funder confidence that you have the ability to do what you are proposing to do?

- Sustainability. And finally, since grants are not for infinite duration but are finite, what will happen when the grant ends? Funders want to be sure that the project will not be terminated as soon as the grant is terminated. You need to show that you can institutionalize the project.

When you sit down to write a proposal, it generally works best to approach the writing task in that sequence. That sequence represents a logic model in which everything flows logically from the need that you have established. Once you have created a need, there should be no surprises introduced into the proposal. Funders do not like surprises; they want things to follow in a logical sequence.

Writing the budget section

When you come to writing the budget, you have a great deal of help into getting your budget figures from the narrative that you have constructed. Once you have written the proposal, the first five sections, you can read it carefully and make notations of each reference to a cost factor and then you can add up the costs. A very useful format for doing this is to use the outline of the federal budget form (SF-505). Whether or not you are seeking an American federal grant or a grant from any other funder, the 505 form is a logical grouping of cross-factors that enables you to capture and explain every cost regardless of what it is for.

Federal form 505. Let us take a look at what is in the federal form 505. Here are the categories: first you start with salaries and those salaries exclude benefits and consultants. There is a reason for doing that. Salaries are expressed in dollar amounts, whereas benefits are generally calculated as a percentage of salaries. Consultants receive benefits and so sorting them out and putting them in a later category facilitates the calculation of the benefits. Category three is all of your travel costs: mileage, airfare, accommodations, meals and any other expenses that are travel related. Line four of the budget is the construction process. Line five is all of your contractual costs, which would include consultants as well as things such as rent, utilities and other contractual items. Things that you are going to purchase are sorted out according to whether they are durable goods, which go into category six, or consumable goods which are category seven. The federal definition is something that will still be usable after three years. Anything that is used up within three years time is considered a supply. Category eight is a residual or any items that do not clearly fit into any of category seven. I almost never have to use that. Category nine is a subtotal of all of the direct costs. Once you have calculated and added up all of your direct costs, you are usually permitted by the funder to apply a percentage of your direct costs as indirect costs. We are going to come back and talk about indirect costs a little later in this hour because they are frequently misunderstood. Finally, you have the grand total of the project. It is a very clear format for presenting a lot of information in a small amount of space.

Four questions about the budget section

Now that you know the budget, how do you present the information to the funder that you are approaching? Let us look at four questions that were raised in the description of this course:

- First, how should salaries and benefits be presented?

- Second, what about the matching funds portion of the grant and the indirect costs portion?

- Third is a very specific question, and that is how specific should your budget be?

- And finally, what are the pitfalls that can turn off a prospective granter? There are many and we will come to those in a little bit.

<membersonly.

Question 1: Salaries and benefits

Let us look at how salaries and benefits should be presented.

As a general rule, like all costs, they should be reasonable. An unreasonableness of budgetary costs is one of the important pitfalls that you want to avoid. You do not want to inflate costs because it will make your project less competitive. It will give the funder the impression that you are not careful with your organization’s money and that you will waste money.

On the other hand, you do not want to lowball your costs, because the funder may fear that you will not be able to accomplish what you set out to do with the funding that you requested. That will put your ability to achieve the results as promised at risk.

If space permits, it is helpful to provide brief job descriptions to show that the work is worth the price. The reason for this is that job titles alone are insufficient. An administrative assistant can be somebody in charge of an office or can be little more than an errand runner. So you need to be clear as to what specific duties that the person holding that title will carry out. One of the things that you need to do is to create a budget narrative to accompany the actual budget figures. The reason for that is to explain costs that might seem to be unreasonable in order to establish the fact that they are reasonable.

For instance, here in New York, costs of doing business and living are much higher than in most parts of this country. I just moved here from Iowa and there you can hire a qualified secretary for fifteen to eighteen thousand dollars a year. Secretaries in New York earn twice that much or two and half times that amount. So a reviewer who is not in New York may look at my budgeted salaries and say that they are exorbitant and so I need to explain that this project is being carried out in an area that has a much higher cost of living than other parts of the country.

Or perhaps my organization operates under a collective bargaining agreement and that mandates a certain level of salaries. Any figures that might conceivably be out of line should be explained so that you can establish that in fact you are not unreasonable.

Question Two: Matching funds and indirect costs

What about the matching funds portion of the grant and the indirect costs portion?

Matching funds

Matching funds are not always required but when they are, the funder wants you to do several things. For one, they want you to show the costs that you are going to assume listed separately from the items that you are requesting funding for. It does not generally work for you to say that the project is a million dollar project and since 30% match funds are required, if you give us seven hundred thousand dollars, we will provide the other three hundred thousand dollars. That normally is a non-starter. They want you to identify specific items of the lined budget that you will pay on your own as well as those specific lines that you want the grant to fund and cover.

Secondly, it is very important that you specify the source of the matching funds you are contributing. It does not work simply to make a promise that if you receive the seven hundred thousand dollars, do not worry about it; we will come up with the other three hundred thousand dollars. You need to explain what the source of the matching fund is. Perhaps you are applying to another foundation. You may be looking for a federal fund for the major funding of your project and you have in mind a private foundation that is going to provide the matching funds. You need to explain who that foundation is and how you know that they are going to make the grant. Again, it is not good enough for you to say that the Ford Foundation or the Rockefeller Foundation will provide the matching funds because it is easy to make promises on behalf of someone else. But how will the funder that you are applying to know that your statement is accurate? You are going to want to attach some documentation from the provider of the other funds. Finally, you want to make sure that your match meets the required threshold. If you are required to make a 30% match and mathematical calculations show that your match is actually 27%, then you have not met the threshold and that can be sufficient reason for a technical rejection of your proposal. So do make sure that you do meet the required threshold of non-grant funding.

"In-kind” matches. If that sounds difficult, here are some good moves for you. Most funders allow, and in fact expect, you to use “in-kind” matches in addition to or in place of cash matches. Here are some examples of “in-kind” matches. If somebody donates labor, any NGO who volunteers to supplement the work done by paid staff, their market value of the donated labor can be used as an “in-kind” match. If there are staff members who are giving a portion of their time towards the project and they are not being compensated for it, you can use their time. Most NGOs have boards of directors. If the board is involved with the project, the value of the board members’ time can be calculated and be charged as “in-kind” match. If equipment is being donated to you, that is a good match. If you are being offered the opportunity to buy equipment for less than its retail value, you can consider as match the difference between the retail price that you would normally pay for it, and the special price that the equipment is being sold to you. Many organizations do not have to rent additional space for a project. They can move the desks a little closer to one another and insert the new project in dedicated space that is already available. That space has value; it is normally calculated on a square footage basis and you can call that “in-kind” match. And any other kind of contribution that has financial value greater than what the project is going to pay for, it is a legitimate “in-kind” contribution.

Very often you are asked to provide twenty or thirty percent of the total project cost as “in-kind” match. In my experience, that should be no problem at all for an NGO to come up with. A lot of the work that NGOs do is work that falls into the category of “in-kind.” Sometimes you are asked to provide a much higher rate of match. I have successfully worked with NGOs to identify matches without any cash commitment that equals grant funds on a dollar-for-dollar basis. It may take a little bit more creativity to come up with 100% “in-kind” match but it is do-able. So do not be intimidated by that. You do not have to provide the entire match in cash money.

Despite the fact that cash match often is not required, it helps to show your credibility of you do provide some cash. It is called in an American idiom: “Putting your money where your mouth is.” You are not simply looking for a handout, but you are willing to contribute to the success of your own project. This same concept is applicable even when matching funds are not required. If you volunteer to provide part of your project’s costs, it shows that you are serious about the project and you are not doing the project simply because money is available but you are willing to put some of your own resources into the project. Even if the match is not required but is being volunteered by you to strengthen your candidacy for a grant, you still need to document to the funder that you have the ability to produce these funds. Because if your budget is a reasonable budget and not an inflated one, you are going to need the funds that you are claiming as match funds to be able to carry out the project. So provide documentation of any claims that you make about your ability to raise non-grant funds. That will help to establish your credibility and to eliminate any doubt about your ability to produce those funds.

Indirect costs

Let us look now at indirect costs, which are often misunderstood. The reason that indirect costs are misunderstood is that there is an incorrect impression that some people have that indirect costs are somewhat of a slush fund.

Let us say that your project’s direct costs are a million dollars and your indirect costs are 10% of the direct funds ($100,000). Those hundred thousand dollars in indirect costs are not extra funds for you to cover any inflation that may occur in-between the time that you submitted your proposal and spent the money. It is not intended to cover the things that you may not have thought of and therefore omitted from the budget.

Rather, indirect costs cover many very actual costs that a project has. Each of them is relatively small but difficult to itemize, yet in the aggregate, they add up. For instance your NGO probably carries liability insurance and other types of insurance. You provide janitorial services to your entire operation. You provide security services, utilities, salaries of administrators who are not directly working on the project that you are seeking grant for, the business office, fiscal management and a multitude of other costs that are each relatively small but that when you aggregate them, they add up to a significant amount of money. Funders recognize that these are real costs, that they are not imaginary costs and they are not fluff. But they are difficult to account for and it is not really practical to itemize them.

Theoretically, you could itemize these items and put them in your budget. But then your budget would be much more unwieldy and would be difficult to view. For this reason, funders permit you to lump them together without identifying each individual item. If you are an American NGO and you have previously received a federal grant, you should have already been given a government-approved indirect cost rate that you can apply to future grants. Normally, indirect costs are about eight or ten percent of your direct costs.

If you are not an American NGO and if you have not received a prior federal grant, then you do not have an approved or negotiated indirect cost rate so you have to guesstimate what that might be. Generally, if you ask for an amount up to ten percent of your direct costs, you will not be challenged because it is considered to be a reasonable amount. Some types of organizations have much higher overhead. For example, universities that have research facilities and extensive buildings and grants and tremendous staff size relative to the direct cost can have indirect costs rates of up to fifty percent and sometimes even higher. If you have a high indirect cost rate that the government has approved, then by all means, use it. If you do not, it is better initially to stick with 10% or so that you do not make yourself less competitive.

Bear in mind that not all funders, federal or private, permit you to recover indirect costs. Some programs expect you to absorb those costs on your own. If you have to do it, it should not be to the detriment of your project. But be aware whether indirect costs are accepted. Also be aware that you can offer to voluntarily wave the recovery of indirect costs if it will make your project more effective.

Question 3: How specific the budget?

The course description said that we would talk about how specific a grant application should be. The answer is you should be as specific as you can within the space limitation.

I have written successful proposals as short as two pages and as long as well over a hundred. Those hundred pages are not the entire proposal but just the main narrative with all of the attached forms. Some proposals that I submit has as much as five hundred pages. Obviously if you have a lot of pages to work with, you can give much more detail than if you have two to five pages, which is what many private foundation funders require.

Make sure that you are aware of and adhere to the page restrictions. If you submit a federal proposal and it says that the limit is twenty five pages and your proposal runs thirty-three pages, some funders will automatically reject your application because it was not responsive and you did not follow the instructions. What other government agencies will do is they will remove pages twenty-six through the end of your proposal so readers will only see the first twenty-five pages. Now if your budget happens to be on pages twenty-seven through twenty-nine, the viewers will not even get to see your budget. You can imagine the effects that will have on your success. The budget may be worth ten points or twenty points out of one hundred on the scoring board that is used. You have automatically forfeited all of those twenty points because the viewers have no information on which to award any points. The two subsequent sections will also receive scores of zero. So make sure that you adhere to the page limitation because it is critical. One amount of detail that you do not want to go to is to use decimal points in your budget. Use whole dollar amounts only; simply round up or down to the nearest dollar and do not use pennies. It is also helpful sometimes, if space permits, to use an executive budget summary as well as a more detailed line-item budget that shows the cost calculations.

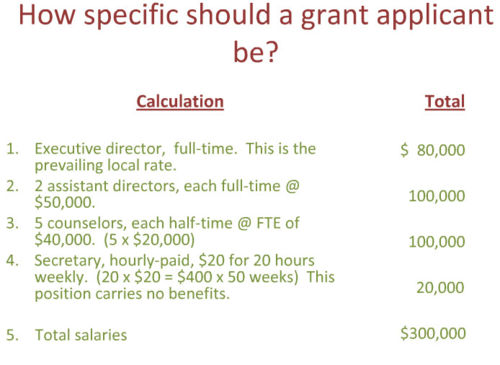

Here is an example of a simple budget narrative explaining items, with four lines designed to make a specific point. In budget line number, listed is “executive director full-time” with the salary. Because the listed salary of $ 80,000 seems high for some people or places, I have explained that that is the “prevailing local rate” in the area that the project is going to run. That is the simplest kind of budget calculation. In line two you have a similar situation except now you have two people holding the same title. In this case it is assistant director. I have shown that both are full-time. I have shown what the full-time salary is: $50,000, and I have multiplied that by my number of positions to arrive at a line item total of $100,000. Line three becomes a little bit more complex. You have five positions but these are not full-time positions, they are half-time positions. So I have shown what the full-time equivalent (FTE) is: $40,000. That is, I listed “5 counselors, each half-time @ FTE $ 40,000 (5 x $20,000),” yielding a total for that third line of $ 100,000. I have taken 50% of that to downgrade those positions to half-time positions and then I have multiplied that by the number of people holding that job title. So five times $20,000 (five half-time positions,) add up to $100,000. In line four I enter a calculation for a person who is paid on an hourly basis rather than on a salary basis. That is, it states “secretary, hourly-basis, $20/hour for 20 hours weekly, $20 x 20 hours = $400 x 50 weeks” for a total of $20,000. have also indicated that that position carries no benefits. When I get to the next part of my budget, the fringe benefits, I will exclude that secretary’s salary from the calculation of benefits. And then I have added up the total for those four budget lines to come to my salary total of $ 300,000.

You do not need to be any more complex than that. It is simple, easy to follow, and it explains how I am arriving at these numbers. I am not simply putting down numbers and leaving the reviewers to guess how I got them.

Major pitfalls

Let us look at some of the major pitfalls that can turn off a prospective grant maker. There are many of them and they are not limited to the budget presentation. We are talking in this session about the budget, but the comments here apply to any portion of the budget.

Funders, as I explained, receive far more applications than they can possibly support. This means that a successful proposal normally has no weaknesses. Any weakness in the budget or any other portion of the budget is sufficient to defeat the prospects of your success. Here are some frequently asked questions about budget strategies.

Pad the budget?

The first question that often comes up is that people who apply for grants know that it is the rule rather than the exception for the funder to reduce the amount that is awarded from the requested amount. Anticipating that this is a likely outcome, “is a good idea to pad the budget out a little so that after it is cut you still have the money that you need to operate the project?” If you need one million dollars for your project, why not ask for $1.2 million so that the funder can cut out a couple of hundred thousand dollars, and you get the amount that you were originally hoping to get? The answer is that that is not a good thing to do. The reason that you should not do it is that funders were not born yesterday. They know what things cost and if you pad your budget, all you will do is let them view your project with suspicion. You do not want them to distrust you. You want to develop a relationship of trust in which they feel you are a reliable recipient of their grant-making. You do not want to do anything that will put that relationship at risk. So do not pad your budget, ask for what you really need.

If in fact the funder says that they are willing to award you a grant but not the full amount, the thing to do is to negotiate downward your scope of activities. If you want one million dollars and you feel that is the amount you need to carry out your project, do not ask for $1.2 million, ask for one million. And if you receive an offer for three-quarters of a million dollars, it is absolutely appropriate for you to say to the funder, “We would like to accept the three-quarters of a million dollars that you are offering, but since we cannot carry out a million dollars worth of activities for a lesser sum, we would like to scale down what we will accomplish. We will reduce the goals and objectives of our project so that we can succeed with the amount you are giving us.” Funders will respect that. They will not say, “No, we are taking back our offer of a grant because you want to change your results proportionately.”

Lowball costs to impress funder?

Here is a follow-up question. Okay, we should not pad our budget, we should be as lean as we can, so “why do we not lowball our costs to impress the funder with our frugality?” No that is not a good thing to do either because the funder really does know how much things cost. You are not the only one applying for a grant; they deal with budgets all the time. If they see a million dollars worth of activity, and you are only asking for three quarters of a million dollars, what they will say to themselves is these folks are not in touch with reality. They do not understand that it will cost them one million dollars. And if we make them a grant of three quarters of a million that they are asking for, they will not have the resources to carry out the project and it is likely to fail.

The best approach is to research how much each item is really expected to cost, and then using the estimate. Budgets are not set in stone and everyone knows that costs fluctuate. They way that you manage in an environment of uncertainty, is because you always are allowed to move funds from one budget line to another. You cannot go back to the funder and say that things cost more than you thought they would, please give us a 10% supplement. However some items will cost more than you thought they would and other items will cost less than you thought they did. And you make budget adjustments on an ongoing basis in order to move funds from one to the other. So perhaps gasoline will cost more than what you budgeted for, but airfares may go down and your plane tickets may cost less. It averages out; things have a way of working out.

One of the areas that many projects save money in is salaries. You budget your salaries for a twelve month period. But suppose somebody who holds a position gives you two weeks notice that they are resigning and it takes you two months to fill the position. For six weeks that job is vacant and you will have saved some money. The money that you have saved from unpaid salary can be used to pay other costs that were higher than anticipated.

Small NGO, big vision

Here is an often asked question: “We are a small NGO and we have a big vision. How much money can we ask for?” The answer is that your project budget should be proportionate to your track record. If you are an NGO with an annual budget of one hundred million dollars a year and you ask for five million dollars for a particular project, that is 5% of your total budget and that is perfectly fine. But if you are an NGO with an annual operating budget of half a million dollars a year, you cannot ask for five million dollars because you do not have the infrastructure to manage that kind of project. Perhaps in a few years you will build up your capacity, which is a good thing to do, but you would not be taken seriously if you ask for a project that is much larger than your current capacity.

Now if you are a small NGO with big plans what do you do? Partner with a bigger NGO that has more resources. Funders like partnerships because they bring stability to a project. They validate your project if you are working with other organizations that are of like purpose.

Numbers do not add up

Remember that proposals are written under often intense deadline pressure. We just mailed off the application and after we did -- oops, we found out that the numbers did not add up right. “That is okay, is it not, it is just a minor clerical problem?” The answer is that it is not okay because the message sent to the funder is that you do not do careful work, you do sloppy work, and you might be sloppy with their funds also. So be careful, not only with numbers but with all parts of your proposal.

Deadline

Here is a question that often arises: “We are up against a deadline, which is midnight tonight. It is now one in the afternoon and we are not going to be able to polish up the proposal, should we submit it or hang onto it?” I cannot tell you exactly what to do; there are benefits in either case. If you get it off, you can get feedback on the funder’s perception of the project. If the project is too rough, then the feedback will only have been the obvious. You will not have benefitted from the critique and will have made a bad first impression.

Dollars or local currency?

And the final question that we are going to cover is: ”Should we present our budget in dollars or in the local currency of the current country?” The answer is you should always present a budget for an American grant in US dollars. Do the conversion at the current exchange rate and present it in American dollars. American funders do not want to operate in foreign currencies.

Open a dialogue with funding agency

One of the suggestions that I make is that long before you submit your proposal, it is good to open a dialogue with a program officer who can steer you in the right direction. Most every federal agency and the vast majority of non-governmental funders, by which I mean private foundations, will speak to you. They want to work with an applicant so that they receive the absolute highest quality of proposals.

When you first have selected a funder as one that you are interested in applying to, you should contact them. Email is usually the best way. Once you have established an email relationship you may want to elevate it with a voice to voice relationship via telephone. If it is not inconvenient for you to get to the funder’s office in person, a face-to-face meeting can help to break the ice.

But the least you can do is to start an email dialogue with a program officer and explain to them what the project is that you are thinking of submitting. Prepare a very brief summary of it – something that can be read in a minute or ninety seconds – and ask whether that funder is an appropriate funder for a project of that nature. You can avoid going down the primrose path in submitting a proposal for a funder that is off the mark for what you want. Once you have opened that dialogue, you can ask more specific questions and get clarification that you are on the right path. One of the reasons that I have a high success rate is that I do not submit the right proposal to the wrong funder. Most funders have very specific interests and no matter how great the project is, if it is not within the purview of that funder, it will not be seriously considered.

Bear in mind that competition for grants is extremely key. Most of the competitions that I enter on clients’ behalf have a win rate somewhere around 2%. This means one successful proposal out of every fifty that are submitted. That is the worst it gets. The best it gets is about one in ten or one in eight with a 10% or 12% funding rate. So there is no such thing as a sure thing in the funding. In order to win 40% of the percent of the proposals that you submit, you have to have an advantage over the other funders. Dialoguing can help get that advantage.

References

This article is based on a presentation by Dr. Michael Gershowitz at the 2010 World Congress of NGOs, an online conference held by WANGO.